Kurdish Quotes

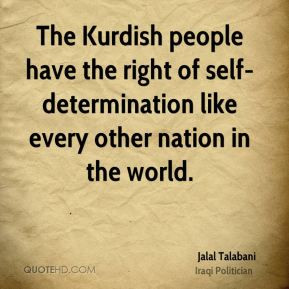

By very conservative estimates, Turkish repression of Kurds in the 1990s falls in the category of Kosovo. It peaked in the early 1990s; one index is the flight of more than a million Kurds from the countryside to the unofficial Kurdish capital, Diyarbakir, from 1990 to 1994, as the Turkish army was devastating the countryside.