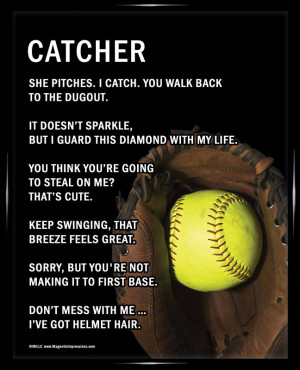

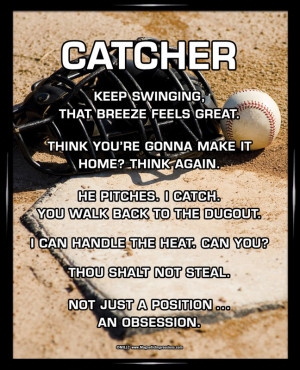

Catcher Quotes

No one intuitively understands quantum mechanics because all of our experience involves a world of classical phenomena where, for example, a baseball thrown from pitcher to catcher seems to take just one path, the one described by Newton's laws of motion. Yet at a microscopic level, the universe behaves quite differently.