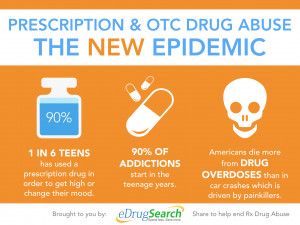

Epidemics Quotes

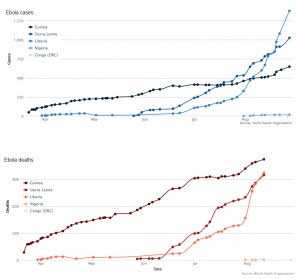

Many diseases including malaria, dengue, meningitis - just a few examples - these are what we call climate-sensitive diseases, because such climate dimensions for rainfall, humidity and temperature would influence the epidemics, the outbreaks, either directly influencing the parasites or the mosquitoes that carry them.